Why This Matters:

- Antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB) represent a major global health threat, and their persistence in the human gut enables both infection and transmission.

- Although antibiotic use is a key selective pressure, ARB can also persist and spread in the absence of antibiotic exposure.

- Identifying the ecological determinants that allow specific incoming ARB strains to establish—particularly the microbiome contexts that promote or prevent colonization—offers critical insight into reducing the gut reservoir of resistance.

- Incorporating these ecological insights into clinical practice can enhance diagnostics, infection prevention strategies, and antimicrobial stewardship by adding a microbiome-informed framework to ARB risk assessment.

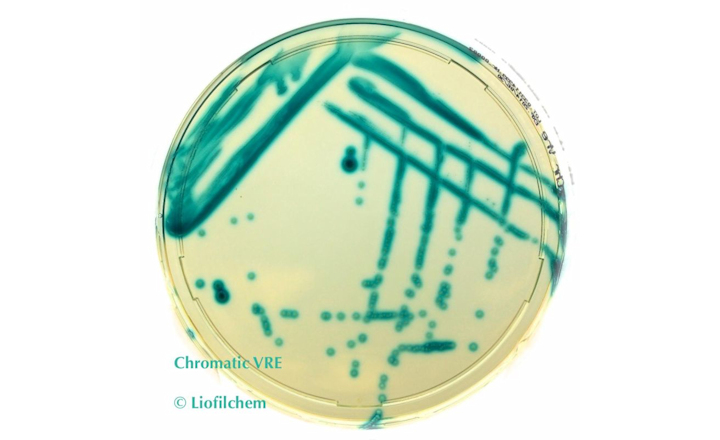

Key Findings: León-Sampedro et al. (2025) used anaerobic human gut–microbiome microcosms to examine how four clinically relevant antibiotic-resistant E. coli strains - harboring ESBL or carbapenemase plasmids—behave with and without antibiotic pressure.1 The authors quantified the contributions of intrinsic abiotic growth, competition with resident E. coli as well as community-level responses to determine what governs establishment of incoming resistant strains. Their data demonstrate that colonization success is highly strain- and context-dependent rather than driven solely by antibiotic selection.

- The 4 resistant E. coli strains exhibited markedly different population trajectories across donor microbiomes, including in antibiotic-free conditions (strain effect: P < 0.001).

- In sterilized abiotic microcosms, the strains showed clear differences in intrinsic growth, supporting a role for baseline abiotic fitness in colonization potential.

- In live microbiome communities, successful establishment required more than inherent growth capacity - competition with resident E. coli and strain-specific effects on community composition were major determinants of outcome.

- Horizontal plasmid transfer from the incoming ARB strains into resident bacteria occurred but was rare, suggesting that strain dominance is a more common route to resistance expansion than plasmid dissemination.

- Metabolic niche breadth, assessed using single-carbon-source utilization assays, did not reliably predict colonization outcomes, underscoring the complexity of ecological interactions in gut microbial communities.

Bigger Picture: This work reframes ARB colonization as the product of layered ecological interactions - not merely a consequence of antibiotic pressure. For clinicians, microbiologists, and infection-prevention teams, the implications are substantial:

- Risk assessment may need to incorporate microbiome ecology, considering which resident species are present, their competitive strength, and overall community resilience, rather than focusing solely on the detection of resistance genes.

- Interventions could extend to microbiome modulation - through pre/probiotics, dietary shifts, or strategies that enhance colonization resistance - to limit ARB establishment in high-risk patients.

- Surveillance and predictive modelling of ARB spread must account for strain-specific traits, community structure, and abiotic fitness, acknowledging that antibiotic exposure is only one piece of the puzzle.

Controlling antibiotic resistance within human microbiomes will require ecology-aware strategies - where preventing colonization becomes as critical as treating downstream infections.

(Image Credit: iStock/Jian Fan)

References:

- León-Sampedro et al. (2025) Multi-Layered Ecological Interactions Determine Growth of Clinical Antibiotic-Resistant Strains within Human Microbiomes. Nature Communications. Volume 16, Issue 9733.